Holes store information as discrete bits with two potential states: the presence or absence of material. Additional information is stored by the location of the hole. Positions across the width of a piano roll correspond to musical notes, with location along the length of the roll defining sequence and duration. Locations across the width of punched tape correspond to the digits of binary numbers. Locations on cards fed into an automated loom correspond to threads in the warp, with a hole indicating that the thread should be lifted allowing the shuttle to pass beneath.

The presence or absence of a hole can be read mechanically, pneumatically, electrically or optically. Holes can also occupy a variety of form factors, including cards, ribbons, sheets and discs. This flexibility has made punched media suitable for a wide variety of applications, e.g., stored software and data, instructions for milling machines, keys for door locks, telegraph messages, census records and votes in national elections.

Letter from Berkeley.The New Yorker, Mar. 13, 1965, p. 52.

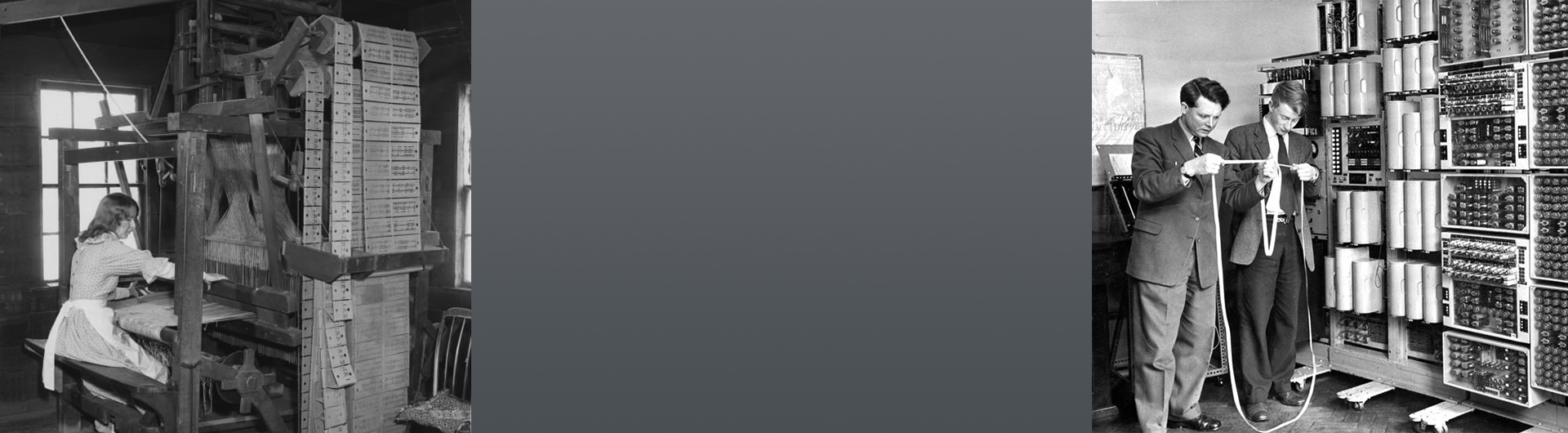

In 1805, building on the work of earlier inventors, Joseph Marie Jacquard used punched cards for the first practical automated loom. Charles Babbage knew of Jacquard's loom and in the 1830s adopted the idea for input and output to his analytic engine (although the engine was never constructed). In 1880, based on Babbage's work and the use of punched cards by train conductors, John Shaw Billings suggested to Herman Hollerith, his fellow employee at the United States Census Bureau, that he come up with a way to use punch cards to tabulate census data (Truesdell 1965, 31). Hollerith went on to invent the machines and processes that dramatically sped up the 1890 census. The company he later founded evolved through a series of mergers into IBM, making Hollerith cards the direct ancestor of the punch cards used for business and computing throughout much of the 20th century.

Punch cards were different from most other ways of storing digital information in two significant respects: they could be overlaid with human-readable text or graphics and they were easily mailable. As a result, punch cards could be sent out into the everyday world to implement human-machine transactions in the form of paychecks, order cards, class registrations, etc. Before the advent of personal computers in the late 1970s, punch cards would have been, for many people, their only direct contact with a computing artifact, something that anyone would at one point or another hold in their hands. As a result, they acquired cultural meaning. In the 1960s, they came to symbolize the commoditization of society, resulting in the rallying cry, "I am a human being; do not fold, spindle or mutilate," based on the warning found on some punch cards.

In first half of the 19th century, Charles Babbage was inspired by Jacquard's automated loom to use punch cards in his difference engine and his (unbuilt) analytical engine. Jacquard's use of punch cards enabled the weaving of elaborate designs that would otherwise have been too slow and labor intensive. The pattern for a weave consisted of potentially thousands of cards strung together in a chain, each card representing one thread in the weft (the crosswise threads). Punch cards for industrial looms have been replaced by computers, but punched media are still sometimes used in home knitting machines.

The punch cards used in business throughout the 20th century changed surpisingly little in format from those introduced by Hollerith. Their size remained approximately the same (with one not very successful exception: the IBM 96-column card). Cards initially had round holes, but eventually IBM chose rectangular holes and the 80-column IBM card became ubiquitous. Remington-Rand and UNIVAC stuck with round holes, although these are seen less frequently.

Storing data in punch cards required specialized punching machines, which made them ill-suited for use outside business offices. One solution was prescored holes, which could be "punched" using a hand-held stylus. This technology was often used for ballots, although hand punching wasn't always reliable. The U.S. presidential election in 2000 was a reminder that modifying physical objects to store information is not guaranteed to work 100% of the time.

Another approach to acquiring data outside the office was to eliminate hole punching entirely. The Mark-Sense system, introduced by IBM in the late 1950s, was developed to allow students to answer exam questions by marking cards with a pencil. Mark-Sense used standard 80-column cards, with every other column left blank to increase the space between the handmade marks. The graphite used in pencil lead was electrically conductive, so the cards could be read by passing them beneath wire brushes that actually came in contact with the pencil mark. Optical readers replaced electrographic technology around 1960. The system was eventually applied to a variety of form factors, including 8½ by 11" answer sheets. The technology, under various brand names, is still used today for answer sheets and election ballots.

Card punches, readers and sorters were too expensive for smaller companies and individuals with simpler needs. Various ways of processing punched data by hand with minimal equipment were developed in response. Edge-notched cards have circular holes around their edges. Each item to be tracked is assigned a card. A hand punch is used to turn a hole into an open notch at locations corresponding to specific fields or attributes describing that item. To select items with a particular attribute, a needle is passed through the stack of cards at the hole corresponding to that attribute. The cards with notches at that location would fall out of the stack when it was shaken. Multiple needles and/or multiple steps could be used to implement AND, OR and other logical operations.

Coding schemes could be quite sophisticated, including the use of hash functions (called superimposed coding at the time) to store alphabetic data like names and codes to represent 10 decimal digits with 5 holes. The literature of the time highlights the importance of information retrieval (a term coined by Calvin Mooers, a computer scientist who developed the influential Zatocoding system for edge-notched cards). A particular challenge was the development of tagging taxonomies that adequately captured the meaning of indexed content.

Optical coincidence cards (also known as "peek-a-boo" cards) invert the principle of edge-notched cards. For edge-notched cards (or punched unit record cards), each item gets a card and the location of notches or punched holes store the attributes for that item. For optical coincidence cards, each attribute gets a card and the location of holes on its interior indicate which items have that attribute. To do a search, a card is selected for each attribute to be searched on. The cards are overlaid on a light table. Light shows through the overlapping holes for items that satisfy all the attributes.

With edge-notched cards (or unit record cards) the number of items is unlimited, but the number of attributes is limited. With optical coincidence cards, the number of attributes is unlimited, but the number of items is limited.

Punch cards were in active use for roughly a hundred years. Over that time they found innumerable applications. Although commonly associated with computers, for the first half of the 20th century—before computers even existed—they were used for accounting and similar data processing applications that required sorting, booking keeping and report generation—what was known as unit record processing. When computers came along, they were quickly adopted for input/output and offline storage. Many of these applications depended on the fact that cards could also hold human-readable information.

Punching holes in a card to store information could be generalized to many different form factors, materials and applications. Because holes are punched into a flat substrate—whether paper, card stock, plastic or metal—both human and machine-readable information could be stored in a single artifact. Holes could be read mechanically, which made them useful in operating non-electrical machinery like door locks or looms. For small amounts of information—phone numbers or radio frequencies, for example—cards could be punched by hand.

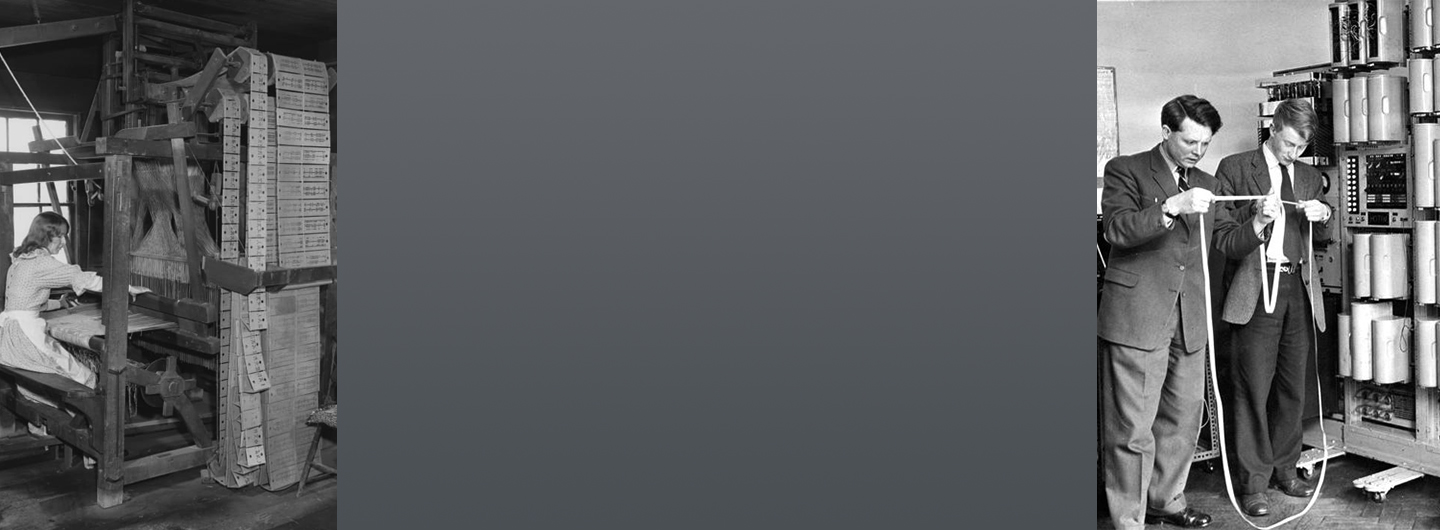

Punched tape originated with the desire to make more efficient use of expensive telegraph lines. Rather than having a telegrapher sit at one end of the line tapping out messages at 30 words a minute, the operator could encode the message offline on paper tape. The tape could then be sent through the machine at 60 or more words per minute. Similarly, more efficient use of computer time could be made if programs and data were encoded offline in paper tape or punch cards, then loaded automatically at high speed. Paper tape also provided offline storage for programs or data that might be used multiple times.

Punched tape formats include two, five, six, seven and eight holes across the width of the tape. Wheatstone, the earliest punched tape format, used two holes to represent the dots and dashes of Morse code. Baudot and its descendants, Murray and IAT2, used five holes to represented alphanumeric and control characters, which gave instructions to operators and teletype machines. Six-hole tape (missing from this collection) encoded extra formatting and characters used in typesetting: the information on the tape could be transmitted from the field to a linotype machine, for example. Seven-hole tape was used for ASCII, which originally consisted of 7-bit codes. Using 8-hole tape expanded the possibilities for ASCII—the extra bit was first used as a parity check and eventually to expand the character set to include upper- or lower-case or non-English characters. ASCII was later replaced by Unicode, by which time paper tape was out of the picture.

The earliest use of paper tape in telegraphy was actually as a visual recording medium. The dots and dashes of Morse code could be captured on tape in ink and read by a human operator at a later time. Hence, paper tape was already in use for storing information when Charles Wheatstone had the idea of punching holes in that tape, which made it machine readable.

Mylar, an alternative to paper, came along in the 1970s when punched tape was frequently used to store computer-generated instructions for CNC machines. Punched tape was more robust than magnetic tape and impervious to magnetic fields, which made it particularly suited to the rough environment of the shop floor. Punched tape was in use for CNC through the 1990s and is still out there today in legacy machinery.

Punched tape was sometimes stored loose with no packaging at all, then loaded directly into the reader by hand. There were a variety of other packages depending on application and environment.

Holes punched in paper were also used in non-computer applications. In these cases, the stored information was not encoded numerically. Instead, it acted as a controller for a machine or device, with each hole directing the machine to perform some action, whether ringing a bell to change classes in a school or inserting vertical space into output from a line printer.

Mechanical music employing cylinders embeded with metal pins originated in the mid-1600s. The use of punched media had to wait until the second half of the 1800s, after their use had been demonstrated in automated looms. Organettes, player pianos and other forms of mechanical music were common in parlors and in public places until they were largely replaced by the phonograph in the early 1900s.

Extended sheets of paper or cardboard could potentially hold more music than discs or cylinders. These were typically mounted on rolls, but could also be stored flat or in endless loops.

Books were more durable than paper rolls, could hold more music than discs and didn't have to be rewound after playing.

Discs were easy to store and to mount and dismount, but held a limited amount of music.

Preparing a piano roll or music box disc for publishing was a specialized task requiring a great deal of skill. There are only a few examples of such media that can be "programmed" by the average person. Two of those are described in the section on pinned media. The examples here allow the user to hand punch a simple tune for a small music box. Irish musician Hannah Peel has composed music for a Kikkerland music box similar to the one below, releasing it in 2010 on a successful EP entitled Rebox.

Human-readable lettering can be stored by punching holes to form characters, in which case the position of the holes relative to each other stores the shape of the characters. In the case of the scrolling message below, a device was required to both scroll the message, which is too long to be viewed all at once, and to provide backlighting.

It was also a common practice to program a computer to punch holes at the beginning of punched tape to identify the contents of the tape. Strictly speaking this use of punched tape doesn't belong in this collection since the text is read directly, not read by the computer, but it's a good example of a computer storage medium that holds both human and computer readable information.