Pictures that move have long been a dream of artists and inventors. The magic lantern, an early form of slide projector, could produce limited motion using levers, pulleys and gears, but a general solution only began to emerge with the invention of the phenakistoscope in the 1830s. That device demonstrated that a rapid sequence of still images, or frames, showing incremental changes to a scene is interpreted by the brain as motion.

Like most inventions, cinema was not the product of a lone inventor. Solutions to many distinct problems were needed: instantaneous photography, incremental film transport, image registration, flicker, and projection. Mechanisms were borrowed from watches and sewing machines. Magic lanterns supplied projection technology, as well as a long tradition of projected storytelling. Advances in materials science also played a role, including celluloid, roll film, safety film, and reversal film. Edison and the Lumières achieved success in large part by assembling and refining technologies from multiple sources.

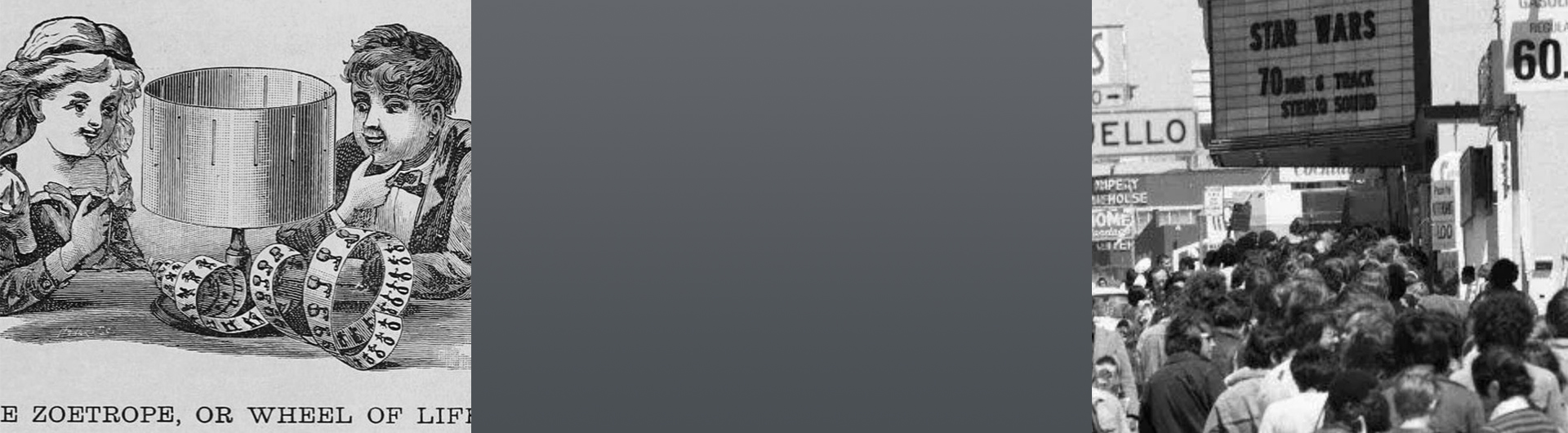

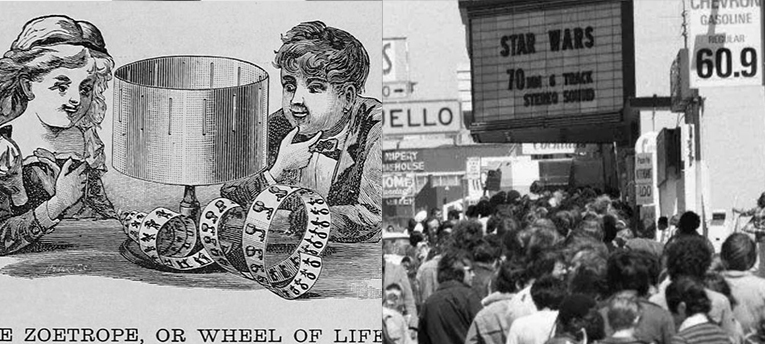

Before the invention of cinema in the 1890s, the phenakistoscope and subsequent inventions used sequences of images to create moving pictures. The images were typically lithographed drawings and only short sequences were practical. From the early 1830s until the invention of cinema, there were three key inventions: the phenakistoscope, the zoetrope and the praxinoscope, each improving on the one it followed.

The phenakistoscope was invented in 1832 by Joseph Plateau, a Belgian physicist, and simultaneously and independently by Simon von Stampfer, an Austrian mathematician. At the time, there was active scientific interest in perceptual illusions related to motion. To investigate one such illusion, the English physicist Michael Faraday constructed a radially slotted disc that spun on a horizontal axis. When held up to a mirror and viewed through the slots, the reflection of such a disc appears unmoving—the reflected slots are visible only when a slot is passing before the eye and are thus always seen at the same position.

Both Plateau and Stampfer were aware of Faraday’s disc. Plateau demonstrated that identical figures drawn on a similar disc, one for each slot, would also appear fixed. He went a step further and intuited that if each of the figures represented a slightly different state of motion, the figures would blend together, creating the appearance of continuous movement (Plateau 1833, 365–368). This proved to be the case when Plateau constructed the device known as the phenakistoscope. He believed the apparent motion resulted from the persistence of the images on the retina. “Persistence of vision” is still often given as the explanation, although it is incorrect—apparent motion is actually the result of visual processing in the brain (Anderson 1993, 3–12; Vaucher 2024).

The phenakistoscope is a successful demonstration of apparent motion, but it has several weaknesses. Only one person can view the image at a time. Also, as Stampfer points out, because the image moves in the time it takes the shutter to pass over it, objects in the animation are stretched horizontally. To reduce this effect, the slots should be as narrow as possible, but this dims the animation, since the eye spends most of its time looking at the opaque areas between the slots (Stampfer 1833, 13).

A zoetrope is a cylinder that spins on a vertical axis. A paper strip with a sequence of images is placed around the interior below regularly spaced vertical slots and the animation is viewed through the slots. As with the phenakistoscope, the slots act as shutters so the images are seen only for short moments at fixed intervals. Unlike the phenaskistoscope, the zoetrope allows multiple people to view the animation at the same time, although it doesn't solve the problem of dim or distorted images.

English mathematician William George Horner first described a version the zoetrope, which he called the daedaleum, in 1834. Several people patented devices zoetrope-like devices in the 1860s. The familiar version and the first to be commercialized was invented by the American William Ensign Lincoln while he was an undergraduate at Brown University. Horner's daedaleum had placed the drawings directly on the cylinder between the slots. Lincoln moved the slots higher on the cylinder so that a separate paper strip with the drawings could be placed below, allowing animations to be easily swapped. He patented it in 1867, giving it the name zoetrope. He licensed it to Milton Bradley, the games manufacturer and it sold extremely well—although Milton Bradley had paid him approximately $125,000 in today's dollars for the idea, Lincoln later wished he had asked for more.

The praxinoscope, invented in 1877 by Charles-Émile Reynaud, replaces the slots of the zoetrope with flat mirrors arranged in an outward-facing circle around the axis of the cylinder. The illustrated paper strip is placed on the interior of the cylinder facing inward, just as with the zoetrope. The animation is viewed by looking at the reflection of the strip in the mirrors. As the cylinder turns, each mirror follows its frame, reflecting it in a relatively fixed location until the next frame comes around. The transition between frames consists of a horizontal “wipe” during which one frame slides over another. There are no intervals of darkness, so the image is brighter than for the zoetrope and phenakistoscope.

Reynaud also developed a projecting praxinoscope. This evolved into the Théâtre Optique, which projected extended animations using frames hand-painted on a long chain of gelatin plates. These were exhibited commercially for several years, but were too labor intensive and couldn't compete with photographic cinema like Edison’s or the Lumières’.

Although the phenakistoscope had demonstrated the principle of apparent motion, true cinema waited on several advances in technology. Photography, invented in the late 1830s, was a virtual necessity. Charles-Émile Reynaud‘s Théâtre Optique, with its chains of hundreds of hand-painting images, was a tour de force that was impractical in general. Before photography could be useful, however, it had to become fast enough to capture at least 16 or so images per second. So-called “instantaneous” photography didn't become routine until the late 1870s. Finally, photographing extended sequences of frames required something other than glass plates; celluloid was invented in 1856 and roll film in 1881.

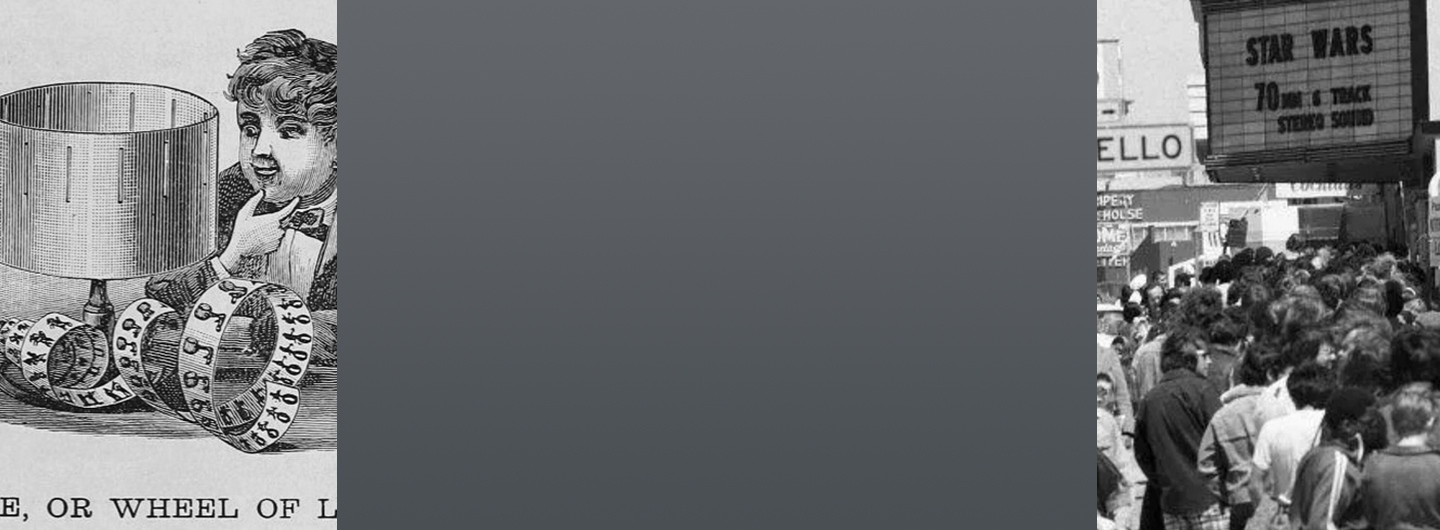

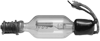

As with many other new media, early inventors were often motivated by scientific goals. Instantaneous photography was taken up by scientists like Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey, who used sequences of images to study human and animal locomotion. With the invention of the Kinetoscope, a nickel-in-the-slot arcade-style viewer, Thomas Edison and his engineer, W. K. L. Dickson brought motion pictures into the world of entertainment and commerce. Edison initially thought that projecting movies would ruin the arcade business and the French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière were the first to implement the entire process of cinema, from camera to projector. Numerous inventors sought to improve the devices and the period was characterized by stealing of credit, patent wars and theft of intellectual property. In the end, no one inventor can be given sole credit. Marey, Edison, the Lumières and others knew each other's work and built upon it.

Although movie theaters replaced magic lantern shows as public entertainment, cinema benefited from the long history of the magic lantern, which provided both projection technology and an audience accustomed to stories and entertainment projected on a screen. Cinema was a continuation of years of what Musser has called "screen practice": techniques for assembling narratives from visual building blocks.

Although Edison had already adopted in 1893 what went on to become the standard format—35 mm, four perforations per frame, 1.33:1 aspect ratio—subsequent years saw a variety of formats differing in gauge(width), aspect ratio (frame width/height), and the number, location and geometry of perforations (or perfs). Sometimes different widths or perforations helped get around patents. Narrower formats also allowed the use of less durable safety film for home movies instead of the highly flammable cellulose nitrate used for 35 mm film. For a discussion of film formats see One Hundred Years of Film Sizes.

The width, or gauge, of film has varied widely over the years—from as small as 3 mm up to 90 mm. Gauge has several implications. A narrower gauge doesn't have to be as strong as a wider gauge, which was important in the days when highly flammable cellulose nitrate was used in theaters. For home use, 28 mm and smaller gauges could be made of less robust and less flammable materials. Wider gauges also spread the image over a larger physical area of the film, thus providing a higher resolution. Finally, narrow gauges were less expensive and the associated equipment smaller and lighter.

The ratio of image width to height, or aspect ratio, can significantly affect the viewing experience. Studios were interested in providing an immersive experience, so over time, aspect ratios tended to increase.

Perforations in cinema film are engaged by a mechanism to advance the film in both the camera and projector. They were the most important contribution to cinema by Edison and, in particular, his engineer W. K. L. Dickson, solving one of its central challenges: to register or align one frame after another precisely in the film gate. The inability to register frames had prevented Marey and others from reliably projecting their chronophotography. Because their cameras couldn't guarantee that frames were equal distances apart, Marey, Le Prince and Skladanowsky were all forced to cut the frames out and assemble them into the final film

Perforations vary in placement and shape. Space taken up by perforations can't be used for the image, so narrower perforations are used in some formats, e.g., Super 8. Narrow gauges have sometimes used a single center perforation on the frame line for the same reason. A soundtrack takes additional space away from at least one side of the film; in the case of 16 mm film, this means that perforationss are dropped entirely on one side. The shape of perforations has also varied to make them less prone to breakage and to improve frame registration.

Film in a movie projector is subject to a variety of abuses: extreme heat from the lamp (a carbon arc lamp for much of the 20th century), tension as it's spooled to and from the reels, stress as it's dragged forward by the sprocket holes and stopped abruptly in the film gate 24 times a second (16 frames per second in the early days of cinema). Commercial cinema standardized on 35 mm film and, at the time of cinema's invention, the only photographic base strong enough at that gauge was cellulose nitrate. Cellulose nitrate has one major drawback, however: it's extremely flammable. It contains its own oxygen and releases it while burning, meaning it can't be smothered—it will even burn underwater. The last place you'd want to position something like that is a few inches from a carbon arc lamp. Theater fires were inevitable—one of the first killed 140 people in 1897. Home cinema got around the problem by adopting narrower gauges requiring less strength from the film base, but commercial theaters used nitrate film until around 1950, when it was finally replaced by cellulose triacetate and, eventually, polyester.

When cinema was invented, the phonograph had been in existence for ten years. The idea of combining motion pictures with recorded sound existed virtually from cinema's inception: in an 1888 visit with Edison, Muybridge suggested combining his zoopraxiscope (a projecting phenakistoscope) with the phonograph. Starting in the early 1900s, two basic approaches were taken: sound-on-disc, in which a phonograph or gramophone is synchronized with the projector, and sound-on-film, where the audio is stored on the film itself by optical or magnetic means.

Early efforts were hampered by inadequate audio technology. Before electronic amplification, phonographs used horns to project their sound acoustically—hardly adequate to fill a theater. The usual recording technique of having the performer stand directly in front of a large horn was a non-starter on a movie set. Microphones existed but were of low quality. It took the invention of the vacuum tube and years of work by film companies and industrial laboratories like Western Electric, RCA and Bell Labs to bring the “talkies” to life.

The first feature-length sound film, released in 1927, used sound-on-disc, but the technology had inherent limitations. Synchronizing a gramophone to a film projector was difficult and unreliable. Records wore out quickly. Recording sound on records also made film editing extremely difficult. By the mid-1930s the industry had moved almost completely to optical or magnetic sound-on-film

The quest for color extended from the birth of photography in 1839 well into the 20th century. Along the way, many color processes, both experimental and commercial, were used to create movies. The earliest examples of color movies didn't involve color photography at all—colors were added by hand painting or stenciling color onto black & white film, or by dipping film in dye baths. (Similar techniques were used with photographs, magic lantern slides and stereoviews.)

Since color photography first appeared in 1861, it has almost always meant storing three channels of light intensity, corresponding to the three types of receptors that sample the spectrum in the eye. The three channels can be combined using additive or subtractive methods. Additive processes store intensity for each color separately, either as three images that are superimposed when projected or by breaking a single image up in various ways into tiny “pixels” storing color information, which are combined by the brain when viewed. Subtractive processes superimpose three transparent images that act as filters to remove the correct amounts of red, green and blue light.

By the time cinema was invented, the stereoscope had been a fixture of middle-class parlors for decades. The evolution of photography and cinema have been driven partly by a desire for ever-increasing realism, and it was natural to imagine moving pictures in stereo, particularly as television began to encroach on the movie business.

3D media (excluding holograms) store the slightly different views seen by each eye as two separate images. In the typical stereoviewer, those images are positioned side-by-side and viewed through lenses that focus each eye on the correct image. But this only works for one person at a time; it isn't useful for an audience. Still, a number of approaches to creating movies for single person viewers were developed—see, for example, the Bünzli l'Animateur below.

Fortunately, there are other ways to store and project the two images. Anaglyph stereo, which had been around since the 1850s, superimposed the left and right images in different colors. The two images could then be separated using glasses with a different color filter for each eye. The colored images could be superimposed on the film itself (subtractive anaglyph) or, more commonly, stored separately on one or two strips of film, projected through color filters and superimposed on the screen (additive anaglyph). Since the early 1950s, the images have instead been projected through polarizing filters and viewed through polarizing glasses.

Any ribbon-like medium stored on reels, whether film, magnetic tape or recording wire, can be tricky to load or rewind. Film can break, jam or unreel itself onto the floor. This was a particular problem for home users, especially children. There were also applications like video jukeboxes that required automatic play, and thus automatic threading. As with audio and video tape, cartridges provided a solution.

Gramophone records and, to a lesser extent, music box discs, had established discs as a practical and familiar format in the home. Movies on disc promised easier handling, simplified loading and more compact storage than film on open reels. Unlike records, however, movies on discs were not successful. A ten inch 78 rpm record could hold around three minutes of music on a side—long enough to hold a popular song. The Spirograph movie disc below had a similar diameter but held little more than a minute of animation, at a time when commercial films were 10 to 50 minutes long. The format remained on the market for only two years.

Closed loops of film simplify threading and are useful for applications requiring continuous presentation.

Although similar in some cases to pre-cinema media, the media in this section are more in the nature of toys than precursers to cinema. In fact, movies had already been invented when these devices were developed. They were intended mainly for children. In some cases, they tell stories, in others, they simply show amusing or surprising actions.

The discs below were viewed using a Geneva drive to hold each frame still for an instant before advancing to the next. This differentiates them from projecting phenakistiscopes like the Ross Wheel of Life, in which the disc rotated continuously.

In barrier-grid animation (also known as “picket fence animation”), an overlay with alternating opaque and transparent vertical stripes is moved over an illustration with two or more frames of animation. (In older versions like those shown here, the illustration moves and the overlay is fixed). The frames are rendered in stripes that match the overlay, with each frame offset by one stripe. Only one of the frames is visible through the overlay at any time. Moving the overlay hides the current frame and reveals the next.

Lenticular animation is similar to barrier grid animation, but instead of a grid, a vertical or horizontal arrangement of cylindrical lenses reveals the alternating strips of the image as it moves. This is the same principle applied in lenticular 3D images, except that here the lenses are in a separate device instead of bonded to the image.

In alternating frames animation, a story is presented as a series of two-frame animations. The operator advances the scroll to the next event and flips back and forth between the two illustrations. In the case of the Minicine, this was carried as far as four frames of animation stored on a plastic filmstrip.

Two states of motion can be stored as different color illustrations, one red and the other blue. When viewed through red and blue 3D glasses, each state is seen by only one eye. Alternately blinking the left and right eye switches between the two states.

The kaleidoscope was invented in 1816 by Sir David Brewster, who later designed the improved stereoscope that kicked off the stereoview craze in the early 1850s. The kaleidoscope generated a similar mania. As with other inventions, adoption (although not the inventor) benefited from widespread piracy. He patented it, but a problem with the patent provided a window for others to begin selling their own versions. Once the kaleidoscope got out into the public, virtually everyone had to have one. And as Brewster observed:

. . . Of the millions who have witnessed its effects, there is perhaps not a hundred who have any idea of the principles upon which it is constructed, who are capable of distinguishing the spurious from the real instrument, or who have sufficient knowledge of its principles for applying it to the numerous branches of the useful and ornamental arts.

Brewster felt obligated to address the lack of scientific understanding with a treatise explaining the fundamentals. It's unclear how many of the millions read it.

A flip book creates an illusion of motion when a viewer flips through a sequence of images on cards bound together in a book. Invented in the 1860s, early flip books didn't require a device, beyond the viewer's own thumb. With the invention of cinema, it became easier to generate large numbers of cards to tell extended stories. Devices like the Mutoscope were developed to flip through hundreds of cards attached to a wheel rotated by a crank. As a card moved past a metal tab, it was held for a moment, then the card flipped out of the way and the next frame was displayed.

Subjects were often excerpts from commercial movies. Much less expensive than the kinetoscope, the Mutoscope and similar devices replaced the kinetoscope as the "nickel-in-the-slot" arcade viewer for movies. Viewers like the Mutoscope survived in arcades into the 1960s.

The Myth of Persistence of Vision Revisited.Journal of Film and Video Vol. 45, No. 1 (Spring).

Sur un nouveau genre d'illusions d'optique[On a New Kind of Optical Illusion]. Correspondance Mathématique et Physique de l'Observatoire de Bruxelles vol. 7 (1833), p. 365–368.

Beyond Persistence: Debunking the Myth and the Science of Animated Motion.animationstudies 2.0. Jan. 9, 2024.